Police crime statistics provide only limited insight into the nature of crime and violence. This is not a uniquely South African problem. The same is true of all police data around the world. For a range of reasons, a lot of crime and violence is never reported to police. This limits the use of relying on police statistics alone to develop interventions to improve public safety.

Fortunately, complementary methods for understanding crime and violence exist. One of these, a victim survey, is well established in South Africa. A second that draws on health data – the Cardiff Model – is in its infancy but developing.

South Africa’s latest Victims of Crime (VOCS – Governance, Public Safety, and Justice) Survey was published on 1 December. This survey explores experiences and perceptions of crime among South Africa’s population.

Unlike police statistics, which only represent crimes reported to and recorded by police, this survey allows us to estimate the percentage of all households and individuals older than 16 who experience crime. It also gauges the rate at which victims report the crimes to police, and asks how safe people feel.

The 2019/20 VOCS estimates that 13.5% of households experienced burglary and 6% of individuals experienced theft of personal property, making these the most common crimes in South Africa. These are also the crimes most commonly reported to the South African Police Service (SAPS).

Concerningly, the second most frequently experienced offences involve the threat or use of violence, namely house robbery and street robbery. According to the survey, these affected roughly 2.5% of households and 2.8% of individuals in 2019/20 respectively.

The VOCS and SAPS measure crime differently. While the VOCS actively seeks out victims, the SAPS waits for them to report. Nor do the two employ the same crime categories or counting rules. As such, although some comparison between the two is possible, it is not precise.

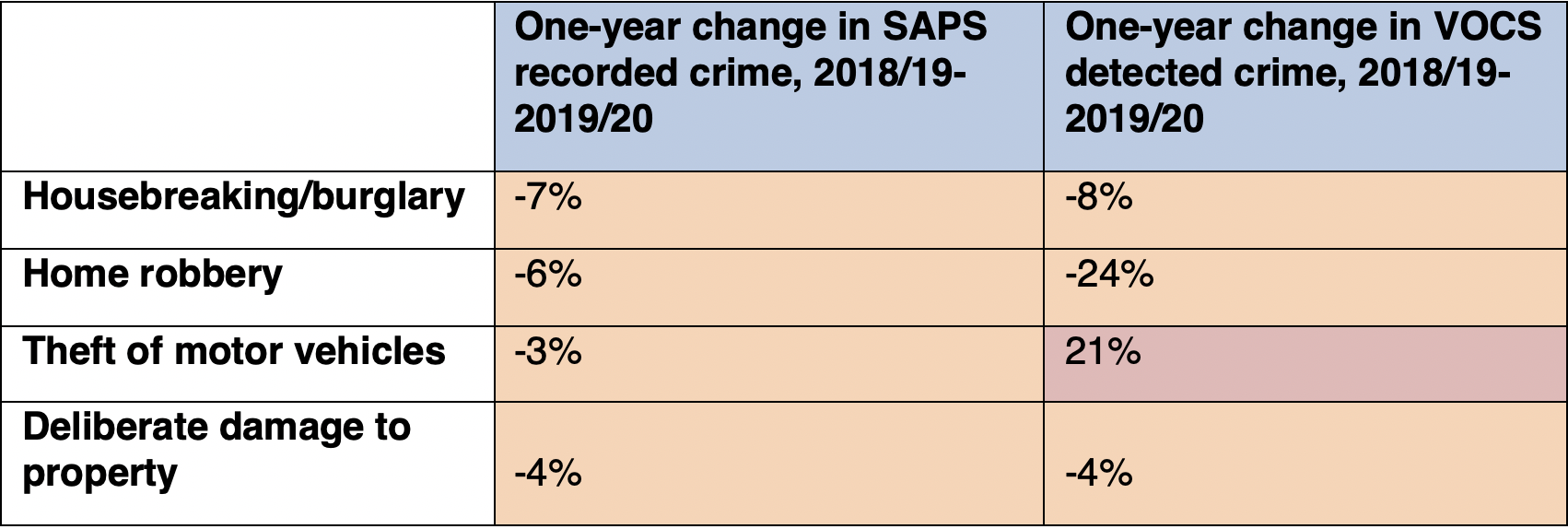

Nevertheless, it is reassuring that year-on-year crime trends in three of the four somewhat comparable categories recorded by both SAPS and the VOCS point in similar directions. Housebreaking, home robbery, and deliberate damage to property all declined. In contrast, the SAPS recorded a decline in theft of motor vehicles while the VOCS detected a substantial increase.

While we can speculate about this difference, for example, more uninsured vehicles being stolen resulting in fewer victims reporting to police – accurately explaining such contradictions requires further research.

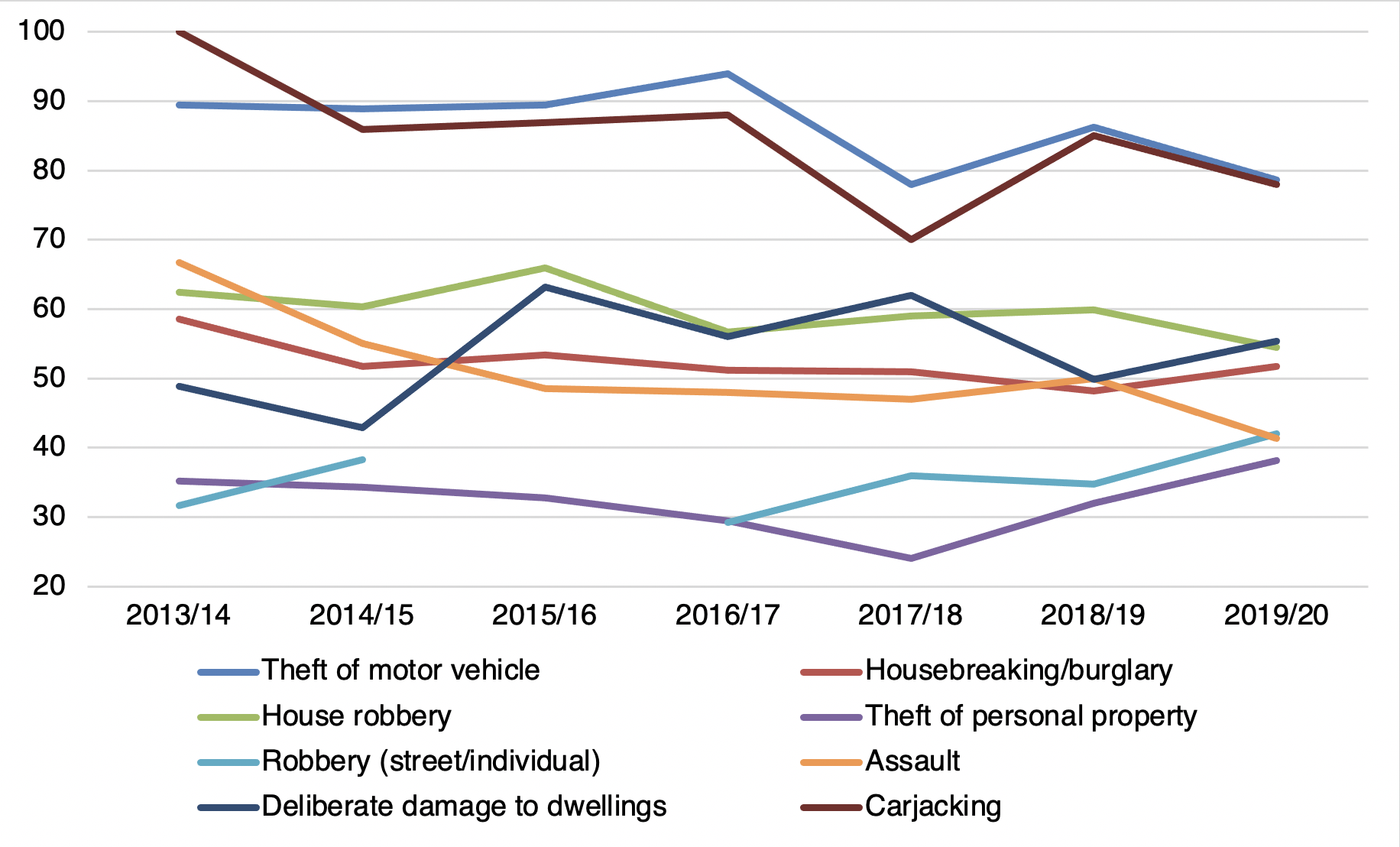

VOCS data shows notable declines in victims’ reporting of crime to police in recent years. For example, in 2013/14, 90% of victims reported their stolen vehicles to police but by 2019/20 only 79% did so. Similar declines are found in hijacking (100% to 78%) and assault (67% to 41%), with less pronounced but important dips in reports of house robbery (62% to 54%).

According to the VOCS, fewer than 45% of all assault, theft or street robbery victims reported crimes to police in 2019/20.

South Africa is fortunate to have an annual VOCS. However, its findings don’t always provide adequate clarity. Furthermore, although VOCS surveys allow for the estimation of millions of offences not reported to police, they do not do so perfectly. For example, many South Africans may not identify an experience as a crime – such as a fistfight with friends in a bar, or being hit with a kitchen pot by a family member.

Not only are many such incidents unlikely to be reported to police, but victims may fail to recall them when asked by a VOCS interviewer whether they have experienced crime in the preceding 12 months or five years.

One useful way to fill this data hole is to capture information on violence-related ambulance calls and trauma admissions at health facilities. As with the fistfight between friends, or the pot assault by a family member, many people seeking medical treatment after violent attacks don’t report incidents to police. Public health data can helpfully improve our understanding of levels of violence. This approach is being piloted in the Western Cape, and should be considered elsewhere.

Finally, the VOCS explores how safe people feel walking alone in their area of residence during the day and after dark. Because this question has been asked in all VOCS since 1998, it is possible to compare the findings over 22 years. Here the 2019/20 data is somewhat positive, with people reporting that they feel safer than at any other time since 1998, other than in 2011.

This may appear counterintuitive in a country with a murder rate six times the global average, but it need not be. Crime and violence are not equally distributed. Some areas and people are significantly more vulnerable than others. So while some communities may be increasingly vulnerable to repeat victimisation, others may be shielded by advances in private security, surveillance technology, and neighbourhood solidarity.

While it is impossible to accurately measure most categories of crime, there is no question that the burden of crime and violence in South Africa is huge. Although neither SAPS nor VOCS data is perfect, the fact that it continues to be captured, recorded and published should be celebrated.

As should Police Minister Bheki Cele’s decision to release quarterly crime statistics, and the Western Cape government’s move to use health data to measure violence. Whatever they reveal, more good-quality data means better ability to effectively understand and intervene in problems, making South Africa safer.

Dr Andrew Faull, Senior Researcher, Justice and Violence Prevention Programme, ISS Pretoria

In South Africa, Daily Maverick has exclusive rights to re-publish ISS Today articles. For media based outside South Africa and queries about our re-publishing policy, email us.